- Details

- Hits: 5275

LIE: "New Study Shows Opioids Never Work for Low Back Pain and Should Never be Used"

A new study came out of Australia the end of June 2023 called OPAL. The authors claim this study proves opioids don't work for low back pain and should never be offered, even as a last resort. The study has major design flaws and also is being seriously misapplied by the authors and media.

This article contains the following information:

- OPAL Study Explained

- Important Links Mentioned

- DPF Patreon Page

- Video Podcast About OPAL

- Audio Podcast About OPAL

- Our Letter to Lancet - and their rejection

A brand new study was published in the Lancet a few days ago. The full pdf of the study is here.

The Opal Trial - Opioid analgesia for acute low back pain and neck pain. This study has already been misapplied and the authors have made inappropriate conclusions based on this tiny flawed study.

This is a brand new study out of Australia. six-week study, around 300 people completed it. They're making the claim that based on this, nobody should ever receive opioids for acute low back pain. No doubt this will be misapplied to all pain, including chronic and post-op.

Dr. Chad Kollas, who is on DPF's board, posted a long helpful thread yesterday, that can help anyone trying to discuss this study. Let us know if you have any questions. This study is already being used as a weapon, so it's helpful to know how to address it.

Here is another updated Twitter thread by Dr. Chad Kollas.

There was a lot of discussion about this study on Twitter. We dug into the study a little bit, and found out that one of the authors of this study also was an author on Australia's deprescribing guidelines that just came out a few days ago. There are a few interesting things about this. First one being a co-author of those guidelines is a US Psychologist named Jason Doctor, who is anti-opioid. He's co-authored articles with PROP members. More interestingly, though, on those guidelines, if you look at the disclosures, you'll see several of the authors are funded heavily by Indivior, maker of Suboxone. Another ridiculous fact is the Lancet asked for specific comment from Dr. Jane Ballantyne and Dr. Mark Sullivan from PROP. The only reason anyone asks for their input is to get the anti-opioid spin.

We knew this trial was rigged. If you look in this article the following statement exists: "“The OPAL trial is a direct response to one of the main findings from The Lancet series: while we have good evidence on harms with opioid analgesics such as addiction, overdose, and death; we have no evidence on whether opioids are effective for a new episode of spinal pain."

The series of studies in the Lancet this study was based on are listed in the link. The last of the series has Roger Chou and Judith Turner as authors. Also, Jane Ballantyne authored a study with the lead author, Christine Lin in 2019. Ballantyne and another author, Maher, spoke together at a conference in 2014.

Our org spent the day looking up information to try to figure out the actual motive. The study itself is kind of odd. They use a medication that's isn't even approved for acute pain in Australia, and wouldn't be used for acute back issues. Watch this two-minute news clip from Australia.

DPF found that Australia has been in the process of suing Pharma over opioids. Why does this matter? Well, it just so happens, the medication they chose to use for this study is a product made by Purdue. Our guess? They're pushing toward lawsuits like we did here in the USA. Oh, and Jason Doctor, one of the authors of the guidelines - he's been an expert witness in litigation in USA.

We will add more to this article as we break down the study.

Here are important links with all of the Lancet articles and OPAL along with supplemental information:

IMPORTANT LINKS

March 21, 2018 Lancet article – “Low Back Pain – A Major Global Challenge pdf

June 9, 2018 Lancet LBP series article – “What LBP is and Why we Need to Pay Attention- Appendix

June 9, 2018 Lancet LBP series article – “Prevention and Treatment of LBP – Evidence, Challenges, Promising Direction” - Appendix

June 9, 2018 Lancet LBP series article – “LBP a Call for Action” - Appendix

December 15, 2018 - Lancet Article – “LBP Authors Reply” Appendix

2018 - Editorial by authors of the Lancet LBP series called "The Lancet series on low back pain: reflections and clinical implications"

March 21, 2019 - Article claiming OPAL was part of Lancet LBP series

July 3-6, 2019 - In the updated call to action published in PAIN, they mentioned An international forum that was held in Canada to discuss the Lancet Back Series and research involved "International Forum for Back and Neck Research."

December 2019 BMJ – Evidence Review –“87 Opioid deprescribing in people with chronic non-cancer pain – a systematic review of international guidelines”

September 2020 - IASP PAIN Journal – “The Lancet Series Call to Action to Reduce Low Value Care for LBP – an Update”

November 14, 2020 Lancet Article – “Lessons Learned from the Lancet LBP Media Strategy”

2022 “Opioid Analgesic Stewardship in Acute Pain -Clinical Care Standard (Australia version of AHRQ)

October 2022- Article published about the International Back and Neck Forum held in 2019 about Lancet LBP Series "Back to the Future: A Report From the 16th International Forum for Back and Neck Pain Research in Primary Care and Updated Research Agenda"

June 15, 2023 “Introduction to Clinical Care Standard for LBP – Australia”

June 25, 2023 Wiley Online Journal – “Clinical Practice Guideline for Deprescribing Opioid Analgesics: Summary of Recommendations”

June 28, 2023 – “Opioid Analgesia for Acute Low Back and Neck Pain (OPAL Trial) – A Randomized Placebo Controlled Trial- Appendix

June 28, 2023 full pdf of OPAL Study

- Details

- Hits: 2479

💥 Debunking the Lie: “Cancer Pain and Non-Cancer Pain Should Be Treated Differently”

⚠️ THE TRUTH:

Pain is pain. There’s no scientific reason to treat it differently based on whether someone has cancer. Yet this false divide has been embedded in guidelines, laws, and policies — not because of medical evidence, but because of stigma, litigation strategy, and political convenience.

📌 TL;DR

- There’s no scientific or physiological difference in how opioids treat cancer vs. non-cancer pain.

- The cancer vs. non-cancer distinction was invented by PROP and others to support restrictive opioid policies and litigation.

- The FDA rejected the distinction as unscientific — but it still made its way into guidelines and laws.

- Even cancer patients are now being denied opioids.

- This arbitrary divide must end. Pain is pain.

📚 Table of Contents

-

The Myth of a Medical Divide

• Where the Split Began: AMDG, CDC, and Policy Language

• PROP’s Citizen Petition to the FDA

• Who Signed the Petition — and Why It Mattered

• Public Pushback and FDA’s Official Rejection

• Why the Distinction Persisted Anyway -

What the Science Says

• “A Distinction Without a Difference”

• Schatman & Peppin on the Flawed Terminology

• The Rise of “Cancer Pain” as a Policy Term

• Why the Diagnosis Doesn’t Change the Physiology -

The Real-World Harm

• April’s Story: When Even Cancer Isn’t Enough

• 2024 Studies: The Pendulum and UW Blog

• Declining Opioid Access and Rising ER Visits

• How Guidelines Are Misapplied to Cancer Patients

• Cancer Patients Facing the Same Stigma -

What Needs to Change

• Eliminate the Distinction from Policy and Practice

• Stop Prosecuting Based on Diagnosis

• Let Clinicians Treat the Patient in Front of Them

• Hold PROP Accountable for the Harm

• Build a New Framework Centered on Compassion and Evidence

📄 Looking for printable versions?

👉 Download the Free Printable Resources from our Patreon page:

🔗 https://www.patreon.com/c/thedoctorpatientforum?redirect=true

1️⃣ The Myth of a Medical Divide

📍 Where the Split Began: AMDG, CDC, and Policy Language

Historically, pain was treated based on its severity, not its cause. Guidelines didn’t divide patients into “cancer” and “non-cancer” groups until the mid-2000s.

-

In 2007, Washington State’s AMDG released the Interagency Guideline on Opioid Dosing for Chronic Non-Cancer Pain. It was one of the first major documents to introduce this split.

-

The 2016 CDC Guideline followed suit, stating opioids should be reserved for “pain outside of active cancer treatment, palliative care, and end-of-life care.”

👉 Read the CDC Guideline

This phrasing would go on to shape state laws, insurance coverage, prescribing limits, and criminal indictments.

🧾 PROP’s Citizen Petition to the FDA

In 2012, the advocacy group PROP (Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing), led by Andrew Kolodny, submitted a citizen petition to the FDA. It requested label changes, but only for non-cancer pain:

-

❌ Remove the word “moderate” from opioid indications

-

📉 Cap the daily dose at 100 MME

-

⏳ Add a 90-day limit on continuous use

🧠 Who Signed the Petition — and Why It Mattered

The petition had over 35 signers, including:

- Andrew Kolodny (PROP President)

- Anna Lembke, MD

- Jane Ballantyne, MD

- Roger Chou, MD — who would later lead development of both the 2016 and 2022 CDC Guidelines

None of the signers provided scientific evidence supporting a distinction between cancer and non-cancer pain. But this framing created a policy wedge — defining one group as “legitimate” pain patients and the other as suspect.

📛 Public Pushback and FDA’s Official Rejection

The FDA convened two major meetings in response:

-

🏛️ May 2012 – NIH Workshop on Opioid Labeling

👉 Meeting Summary -

🗣️ February 2013 – FDA Public Hearing

👉 View the docket and comments

🔹 ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists):

“Non-cancer pain is impossible to define. Cancer survivors often live with chronic pain caused by treatment.”

🔹 Dr. Bob Twillman:

“When does cancer pain become non-cancer pain? After remission?”

🔹 American Cancer Society:

“Opioid receptors don’t know or care whether someone has cancer.”

📄 Why the Distinction Persisted Anyway

Despite the objections, PROP’s framing took hold. In September 2013, the FDA responded:

“FDA knows of no physiological or pharmacological basis upon which to differentiate the treatment of chronic pain in cancer patients from the treatment of chronic pain in the absence of cancer.”

👉 Read the full FDA response

Even though the FDA rejected it, the distinction persisted — not because it was medically valid, but because it was politically and legally useful. It allowed:

- Lawmakers to restrict opioid access while claiming to protect cancer patients

- Insurers to deny coverage

- Prosecutors to build cases based on whether a patient’s pain was “cancer-related”

- The groundwork for the MDL - leading to the $60 billion you see flowing

2️⃣ What the Science Says

🧠 “A Distinction Without a Difference”

In 2016, a Pain Medicine article titled “Chronic Cancer vs. Non-Cancer Pain: A Distinction Without a Difference?” challenged the growing divide between cancer and non-cancer pain. The author explained how the term became a “sham distinction” — a logical fallacy that appeals to a difference where none meaningfully exists.

“When it comes to cancer and non-cancer pain, one really must question why we are drawing a distinction between these two entities — and whether it is science or politics that demands there be a difference.”

The piece also showed that the terms “cancer pain” and “non-cancer pain” only became common in the literature in recent decades — a politically motivated shift, not a scientific one.

🧾 Schatman & Peppin on the Flawed Terminology

In another 2016 article titled “Terminology of Chronic Pain: The Need to Level the Playing Field”, pain experts Dr. Michael Schatman and Dr. Brian Peppin argued that the cancer vs. non-cancer split had no medical basis:

“A patient with pain from a cancer etiology has no different physiology than a patient with pain of non-cancer etiologies.”

They suggested the real meaning behind the distinction could be interpreted as:

-

“We don’t care if the cancer patient suffers side effects from opioids...

But we do care if a chronic pain patient develops these problems.” -

“We don’t care if patients with non-cancer pain suffer.

They are not ‘worth’ the effort of adding opioids to their regimens.”

Schatman and Peppin urged clinicians and policymakers to abandon these biased categories in favor of a more humane, patient-focused language system.

📈 The Rise of “Cancer Pain” as a Policy Term

The terms “cancer pain” and “non-cancer pain” weren’t widely used until the late 20th century. According to the Pain Medicine article, usage of these terms in the literature spiked in the 1990s and 2000s, not because of a scientific breakthrough — but as part of a shift in how chronic pain was framed in public health discourse. This linguistic shift allowed guidelines and laws to differentiate who “deserved” opioids and who didn’t — despite no evidence that opioids work differently in either group.

⚠️ Why the Diagnosis Doesn’t Change the Physiology

Even the FDA said there’s no physiological or pharmacological difference in how opioids treat pain in cancer vs. non-cancer patients. Yet the distinction stuck, becoming embedded in policy. The result? Guidelines and laws justified denying pain relief to entire patient populations — based not on evidence, but on narratives about morality, survivability, and risk.

💔 April’s Story: When Even Cancer Isn’t Enough

For years, we believed that cancer patients were “safe” from the opioid crackdown — protected by the policy carveouts. But reality tells a different story. Take April, a terminal cancer patient who was denied opioid medication at the pharmacy — despite being in palliative care. She shared her story before she passed away, exposing a truth we can no longer ignore: even patients with cancer are being cut off.

This isn’t an isolated incident. It's part of a growing pattern.

Two new publications highlight the shrinking access to opioids — even for cancer patients.

🔹 A 2022 study in JAMA Oncology found that from 2007 to 2017:

- Opioid prescribing for poor-prognosis cancer patients declined significantly

- Pain-related emergency department visits increased

- Researchers concluded that end-of-life pain management may be worsening

🔹 A 2024 article in Dove Medical Press warned of a troubling shift. In a piece called "The Pendulum", authors urged policymakers to stop overcorrecting and start protecting access to appropriate opioids for cancer patients — before more people suffer.

🔹 And a 2024 UW Medicine blog asked whether chronic cancer pain should still qualify for opioid therapy at all, signaling another step toward restriction.

🚪 Cancer Patients Now Face the Same Barriers

The idea that cancer patients still “get opioids” isn’t just outdated — it’s dangerous. Today, they face many of the same barriers as people with chronic non-cancer pain:

- Pharmacist refusals

- Red-flagging in the PDMP

- Insurance denials

- Doctors afraid to prescribe

- Accusations of drug-seeking

- Misinterpretation of “safe prescribing” guidelines

The stigma and scrutiny that once only applied to “non-cancer pain” has crept into oncology, palliative care, and even hospice settings.

🔄 How Guidelines Are Misapplied

Guidelines like the CDC’s were supposed to exclude cancer, palliative, and end-of-life pain — but these exclusions mean little in practice.

-

Some clinicians mistakenly apply the CDC guidelines to all pain

-

Others fear scrutiny or liability, regardless of diagnosis

-

Many institutions create blanket policies to avoid risk altogether

As a result, patients who should be protected are often left unmedicated, suffering from untreated or under-treated pain.

😔 Stigma Doesn’t Stop at the Cancer Diagnosis

A 2023 study in JAMA Network Open explored oncologists' attitudes about prescribing opioids for cancer-related pain. Key findings:

- Patients report feeling stigmatized — by providers, pharmacists, and the public

- Many fear addiction, which affects their willingness to take prescribed opioids

- Prescribers often misunderstand or misapply safety guidelines

Even terminally ill patients are sometimes denied care due to the opioid climate. And cancer survivors — dealing with chemotherapy-induced neuropathy or post-surgical pain — often no longer qualify for “cancer pain” protections, even though their pain stems directly from cancer treatment.

4️⃣ What Needs to Change

🧹 Eliminate the False Divide from Guidelines and Laws

There is no scientific reason to treat cancer pain and non-cancer pain differently when it comes to opioid access. This arbitrary distinction should be:

-

Removed from clinical guidelines like the CDC opioid prescribing guidance

-

Eliminated from insurance policy exclusions

-

Banned from being used in legal indictments or regulatory decisions

Pain relief should be based on the needs of the individual — not whether their diagnosis fits a government-created exception.

⚖️ Stop Prosecuting Based on Diagnosis

Doctors have been criminally prosecuted for prescribing opioids to people with “non-cancer pain” — while cancer patients were carved out as more “acceptable.” But this approach is:

- Ethically indefensible

- Medically meaningless

- Legally arbitrary

Diagnosis-based exemptions are a tool of convenience — not science. We must stop using the absence of cancer as a reason to punish providers and abandon patients.

🩺 Let Clinicians Treat the Patient in Front of Them

Every patient deserves a care plan based on their condition, their risks, and their preferences — not a label. Providers should be trusted to:

- Assess pain on a case-by-case basis

- Use clinical judgment when deciding whether opioids are appropriate

- Document reasoning without fear of punishment

Blanket policies that treat all non-cancer pain as unworthy of opioid treatment are both cruel and ineffective

The harm from the cancer vs. non-cancer distinction was not accidental. It was introduced by PROP and its allies to build a framework for:

- Cutting off long-term opioid prescribing

- Supporting mass tort litigation

- Creating a “safe” political carveout to shield backlash

This distinction gave public health officials and legal actors cover — but it cost patients their care. There must be transparency and accountability for those who manufactured this division.

🛠 Build a New Framework Centered on Compassion and Evidence

We need pain care policy that:

- Respects all patients — regardless of diagnosis

- Rejects moral hierarchies in pain treatment

- Recognizes that suffering is suffering, whether it comes from cancer, trauma, injury, or chronic illness

- Ends the use of unscientific categories as gatekeeping tools

The system must evolve from distinction-based denial to compassionate, patient-centered care.

5️⃣ Citations

📚Full Formatted Citations

-

Washington State Agency Medical Directors’ Group. (2007). Interagency Guideline on Opioid Dosing for Chronic Non-Cancer Pain. https://www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/files/opioid/dosingguideline.pdf

-

Dowell, D., Haegerich, T. M., & Chou, R. (2016). CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain — United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep, 65(1), 1–49. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/rr/rr6501e1.htm

-

Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing (PROP). (2012, July 25). Citizen Petition to the FDA Requesting Label Changes for Opioid Analgesics. https://downloads.regulations.gov/FDA-2012-P-0818-0001/attachment_1.pdf

-

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2013). Response to PROP Petition. Docket No. FDA-2012-P-0818-0793. https://www.regulations.gov/document/FDA-2012-P-0818-0793

-

Ballantyne, J. C., et al. (2012). Assessment of Analgesic Treatment of Chronic Pain: A Scientific Workshop Summary. NIH/FDA. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4500186/

-

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2013, Feb 7–8). Impact of Approved Drug Labeling on Chronic Opioid Therapy: Public Hearing. Federal Register Notice. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2012/12/19/2012-30516/impact-of-approved-drug-labeling-on-chronic-opioid-therapy-public-hearing-request-for-comments

-

Docket FDA-2012-P-0818. Public Comment Archive on Opioid Labeling Petition. https://www.regulations.gov/docket/FDA-2012-P-0818

-

Pain Medicine. (2016). Chronic Cancer vs. Non-Cancer Pain: A Distinction Without a Difference? 17(5), 890–898. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4879076/

-

Schatman, M. E., & Peppin, J. F. (2016). Terminology of Chronic Pain: The Need to Level the Playing Field. Journal of Pain Research, 9, 1057–1064. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27493799/

-

Enzinger, A. C., Ghosh, K., Keating, N. L., & Cutler, D. M. (2022). US Trends in Opioid Access Among Patients With Poor Prognosis Cancer Near the End-of-Life. JAMA Oncology. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology/fullarticle/2796635

-

Farooqi, F., Karim, M. R., & Balaban, A. (2024). The Pendulum: The Need to Develop a Safe, Effective, and Equitable Management Strategy for Opioids in Cancer Patients. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 17, 275–282. https://www.dovepress.com/the-pendulum-the-need-to-develop-a-safe-effective-and-equitable-manage-peer-reviewed-fulltext-article-RMHP

-

University of Washington Department of Anesthesiology & Pain Medicine. (2024). Distinguishing Chronic Cancer Pain From End-of-Life Pain. https://anesthesiology.uw.edu/distinguishing-chronic-cancer-pain-from-end-of-life-pain/

-

Paice, J. A., et al. (2023). Oncologists’ Views on Challenges in Opioid Prescribing for Cancer Pain. JAMA Network Open, 6(1), e2252014. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2815766

🖨️ Printable Resources

For free printable resources, go to our Patreon Page. You will need to subscribe (free) to access printable free resources.

Included Printable Resources:

-

✅ Condensed Summary of Main Points

A quick-reference overview of why the cancer vs. non-cancer pain distinction is flawed and harmful. -

🧠 Myths vs. Facts Handout

A side-by-side breakdown of common misconceptions and the truth behind the science and policy. -

❓ Q&A Sheet

A clear, patient-friendly guide answering the most common questions about the cancer vs. non-cancer divide. -

📚 Full Citations List

All sources referenced in the article, formatted and linked for easy access and credibility.

- Details

- Hits: 3107

💥 Debunking the Lie: “Studies Show Opioids Don’t Work for Chronic Non-Cancer Pain”

🚫 Debunking the Space Trial Claim

Krebs, E. E., Gravely, A., Nugent, S., Jensen, A. C., DeRonne, B., Goldsmith, E. S., ... & Noorbaloochi, S. (2018).

Effect of opioid vs nonopioid medications on pain-related function in patients with chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain: The SPACE randomized clinical trial.

JAMA, 319(9), 872–882.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.0899

Free Printable Resources: Please subscribe (free) to our Patreon Page

⚡TL;DR - The Truth About the Space Trial

The 2018 SPACE Trial is often used to claim that “opioids don’t work” for chronic pain. But that’s a gross misrepresentation of what the study actually showed.

THE CLAIM:

The 2018 SPACE Trial “proved” that opioids are ineffective for chronic pain.

THE TRUTH:

The SPACE Trial showed both opioids and non-opioids worked — and neither group was superior for function. The trial excluded most chronic pain patients, used low opioid doses, and still found no cases of addiction, OUD, or death.

Despite this, the study was spun by media, regulators, and expert witnesses to justify policies that have devastated pain patients — including forced tapers, medication denial, and criminalization of care.

This wasn’t science. It was strategy.

📚Table of Contents

- Intro: Debunking the SPACE Trial Narrative

- What the SPACE Trial Actually Found

- How the Narrative Was Spun by Media and Advocacy Groups

- Who Benefited: Conflicts, Litigation & Paid Experts

- How It Was Misused to Harm Patients

- What the Study Really Means

✅Section 1: Debunking the SPACE Trial Narrative

In 2018, a study called the SPACE Trial was published in JAMA and quickly seized by media outlets, addiction advocates, and policymakers. They claimed it “proved” that opioids are ineffective for chronic pain, especially long-term. This single study was cited in headlines, courtrooms, federal guidelines, and insurance policy changes — despite being limited in scope, deeply misrepresented, and filled with nuances the public was never told about.

The result? Millions of people living with severe pain were denied treatment, tapered off stable doses, or forced to try medications that didn’t work — all because of how this one study was spun. The SPACE Trial became a blunt weapon in a war on pain care. This article sets the record straight — not just on what the study actually found, but on who benefited from its distortion, and why pain patients are still paying the price.

📊Section 2: What the SPACE Trial Actually Found

The 2018 Strategies for Prescribing Analgesics Comparative Effectiveness (SPACE) Trial was a randomized study of opioid vs. non-opioid medications in 240 U.S. veterans with chronic back pain or osteoarthritis (OA) of the hip or knee. It was published in JAMA and quickly weaponized to claim that “opioids don’t work for chronic pain.” But when you actually read the study, that’s not what it shows.

🧪 Study Design

- Conducted within the VA system (2013–2015)

- 12-month comparison of opioid vs. non-opioid therapy

- Patients had chronic back or OA pain (moderate/severe)

- All participants were opioid-naïve

- The trial used a “treat-to-target” approach — adjust meds to improve function

- Primary outcome: Pain-related function

- Main secondary outcome: Pain intensity

Who Was Excluded?

The trial excluded most of the chronic pain population, including:

- People with fibromyalgia, migraines, or other complex conditions

- Anyone already on chronic opioid therapy

- Patients with mental illness or substance use disorder

- Those using benzodiazepines

- People with other pain types, including visceral or neuropathic pain

- 87% of participants were male

Of 4,485 patients screened, only 265 enrolled

- 1,843 declined

- 2,377 excluded based on diagnosis, medication history, or comorbidities

Yet despite this narrow scope, the study is often used to justify restrictions on all chronic pain patients.

What Medications Were Used?

The opioid group received:

- Immediate-release morphine, oxycodone, or hydrocodone/acetaminophen

- Some were transitioned to extended-release meds or fentanyl patches

- Average daily dose: ~22 MME. This is well below therapeutic doses typically used for moderate-to-severe pain

The non-opioid group received:

- Acetaminophen, NSAIDs

- Adjuncts: duloxetine, gabapentin, nortriptyline

- Tramadol (an opioid) was used in up to 11% of patients by month 12

- The non-opioid group received more medications overall

The comparison was far from apples-to-apples — low-dose opioids were pitted against high-dose combinations of multiple meds, including another opioid.

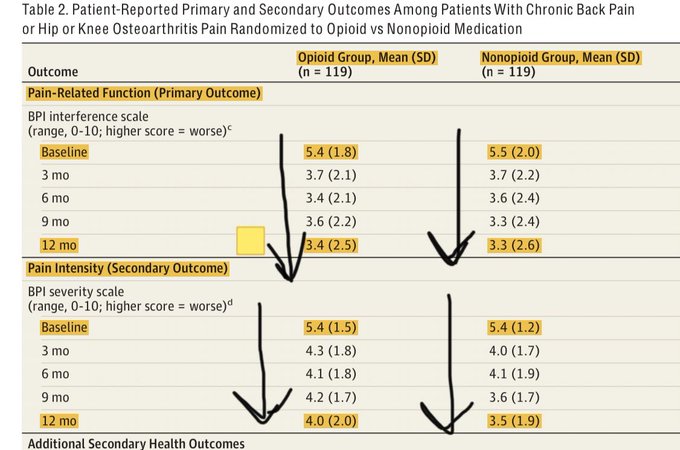

What Were the Results?

✅ Pain-Related Function (Primary Outcome)

Both groups improved

No significant difference at 12 months

-

Opioid group: 3.4

-

Non-opioid group: 3.3

-

(On 0–10 scale; higher = worse function)

-

Over 59% in each group had a ≥30% improvement in function

Pain Intensity (Secondary Outcome)

-

Slightly better in the non-opioid group

-

Opioid: 4.0

-

Non-opioid: 3.5

-

Statistically significant, but clinically small (~0.5)

-

Other Outcomes

- Anxiety scores improved more in the opioid group

- Quality of life scores were similar between groups

- Adverse effects (e.g., constipation, nausea) were more common in opioid group, but generally mild

- No deaths, no OUD, no doctor shopping, no diversion

🧠 What This Means

The SPACE Trial did not show that opioids are ineffective.

It showed that:

- Low-dose opioids and multi-drug non-opioid therapy had similar results

- Opioids were not more dangerous in terms of addiction, misuse, or death

- Anxiety was slightly better in the opioid group

- The differences in pain scores were small, and both groups benefited

This was a small, VA-based trial of opioid-naïve men with specific types of pain — not a referendum on treating all chronic pain conditions.

⚖️ The Litigation Narrative Begins Here

Despite its narrow scope and balanced findings, the SPACE Trial was immediately spun to support opioid lawsuits, with expert witnesses like Anna Lembke testifying under oath that:

“Researchers… were forced to conduct studies to counter the pharmaceutical companies’ opioid promotions. Those studies found that opioids were not effective for the long-term treatment of moderate to severe pain…”

But, the SPACE Trial showed opioids were effective — and that none of the 240 participants developed addiction. This is a continuation of a litigation-driven narrative that would later shape policy, funding, and widespread tapering — all built on a misrepresentation of the actual data.

📰 Section 3: How the Narrative Was Spun by Media and Advocacy Groups

Within days of its release, the SPACE Trial wasn’t just discussed — it was weaponized.

The findings, which showed that opioids and non-opioids performed similarly, were stripped of context and transformed into clickbait headlines and talking points for policy advocates, health agencies, and expert witnesses pushing for opioid elimination. The result? A misleading narrative that opioids “don’t work” — repeated so often it became accepted truth.

What the Headlines Claimed

Mainstream outlets ran with oversimplified — and in some cases, flat-out false — interpretations:

-

Vox: “Opioids are no better than other medications for some chronic pain.”

Source -

NPR: “Opioids are overrated for some common back pain, a study suggests.”

Source

🔍 These headlines implied that:

- Opioids don’t help at all

- They were clearly inferior

- They’re being overprescribed to people who don’t need them

None of that is supported by the actual trial data.

How PROP and Advocacy Groups Amplified It

Groups like PROP (Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing) immediately used the study to support restrictive guidelines and lawsuit narratives.

In one PROP newsletter, they falsely claimed:

“The best evidence now shows that prescription opioids are ineffective for long-term management of common chronic pain conditions, such as osteoarthritis and low back pain.”

📌 But in the actual SPACE Trial:

- Both groups improved in pain and function

- No one developed addiction

- Function outcomes were equal

- Anxiety was better in the opioid group

Even duloxetine, gabapentin, and tramadol (an opioid) were used in the so-called “non-opioid” group — making the claim of opioid inferiority completely unsupported.

How This Became Legal & Policy Ammo

Policy influencers and expert witnesses — many of whom were also affiliated with PROP or paid by law firms — used these distorted claims to:

- Justify the CDC’s 2016 opioid guideline

- Support the VA and DoD “opioid-sparing” push

- Promote the idea that prescribing opioids equals harm

- Testify in opioid litigation that these findings prove opioids should not be used for chronic pain

This was the origin of the narrative we hear today:

“Opioids are ineffective. They're dangerous. They must be eliminated.” It didn’t come from the study itself. It came from those with something to gain — legally, politically, and financially.

💰Section 4: Who Benefited: Conflicts, Litigation, and Paid Experts

The misrepresentation of the SPACE Trial didn’t just happen in a vacuum. It happened because it served powerful interests — from expert witnesses in opioid lawsuits, to advocacy groups like PROP, to industries profiting from opioid elimination.

Litigation Strategy in Action

The SPACE Trial was cited repeatedly in opioid litigation, used to argue that opioids were ineffective and overprescribed. But it wasn’t just cited — it was directly shaped into a legal weapon.

Under oath in New York opioid litigation, Dr. Anna Lembke testified:

“Researchers, including those who published an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2018, were forced to conduct studies to counter the pharmaceutical companies’ opioid promotions.”

She went on to claim:

“Those studies found that opioids were not effective for the long-term treatment of moderate to severe pain.”

🛑 Neither of those statements is accurate.

The SPACE Trial showed:

-

Opioids were effective for many patients

-

No one developed addiction or misuse

-

There was no overdose, diversion, or doctor-shopping

Lembke also testified in the same case that she earned $500–$800/hour as an expert witness, and admitted to earning hundreds of thousands of dollars doing so.

Judicial Pushback

Lembke’s claims have been challenged in court. In a 2022 California case, Judge Peter Wilson ruled that she:

“Overstated the risk of addiction”

And her testimony was “inconsistent with the evidence.”

Yet she continued to testify in other states, using the same flawed narratives — often based on the misrepresented SPACE Trial.

PROP, Guidelines, and Industry Ties

PROP (Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing) also benefited from the study’s spin:

- PROP’s members helped write the 2016 CDC Guidelines

- They frequently referenced the SPACE Trial as evidence that opioids don’t work

- Several PROP-affiliated experts served as paid litigation witnesses in opioid lawsuits

In one newsletter, PROP claimed:

“The best evidence now shows that prescription opioids are ineffective for long-term management of common chronic pain conditions.”

This directly contradicts the actual study, where:

- Both groups improved

- Function was the same

- No OUD cases were detected

Abatement Money: The More Diagnoses, the More Dollars

In opioid lawsuits, settlement abatement funds were distributed based on the number of people diagnosed with opioid use disorder (OUD). The more people labeled with OUD, the more money states and counties received.

This created a perverse incentive:

- Misclassify pain patients as having OUD

- Use inflated misuse stats to secure funding

- Justify denying opioids and promoting “treatment” (often Suboxone) even in cases where addiction wasn’t present

The SPACE Trial, when spun to suggest opioids “don’t work,” became part of that narrative — even though the actual study found no OUD or misuse.

Who Gained

- Litigators made billions in settlements

- Addiction pharma companies gained market dominance (e.g., Suboxone)

- Expert witnesses were paid hundreds of thousands

- PROP-aligned policymakers pushed restrictive guidelines

- “Anti-opioid” groups got grants, funding, and influence

Who lost? Chronic pain patients — cut off, tapered, misdiagnosed, and forgotten

🩹Section 5: How it Was Misused to Harm Patients

The distorted narrative around the SPACE Trial didn’t just stay in courtrooms or academic journals. It was used to justify sweeping, dangerous policies that cut off care to millions of pain patients — many of whom were never even part of the population studied in the trial.

Misapplied to the Wrong Patients

Although the SPACE Trial:

- Included only opioid-naïve veterans

- Focused only on back and OA pain

- Excluded people with fibromyalgia, migraines, mental illness, or prior opioid use

- Used low-dose opioids (~22 MME/day)

Its conclusions were broadly applied to:

- Patients on high-dose, long-term opioid therapy

- Women with endometriosis, lupus, CRPS

- People with sickle cell disease, cancer survivorship pain, and rare disorders

- Patients already dependent on opioids for basic function

Policies were enacted as if this trial proved that opioids don’t work for anyone. They didn’t — and it didn’t.

Used to Justify Forced Tapering

The SPACE Trial became a go-to citation for:

- Insurance companies denying coverage for opioid therapy

- Doctors tapering patients against their will

- Hospitals cutting off post-surgical opioids

- Regulators punishing physicians who prescribed above “low-dose” levels

- Never mind that the trial:

- Found no cases of OUD or misuse

- Reported better anxiety scores in the opioid group

- Involved none of the patients now being tapered or abandoned

What Was Actually Found?

Let’s be clear about what the study showed:

Yet somehow, this was twisted into “Opioids don’t work” and “They’re too dangerous to prescribe.”

Quotes That Prove the Misuse

PROP Newsletter:

“The best evidence now shows that prescription opioids are ineffective for long-term management of common chronic pain conditions…”

Anna Lembke (interview):

“If opioids worked long-term, I would have no problem with patients taking them… [but] they stop working and then you have an additional problem.”

But her own citation — the SPACE Trial — showed they do work for many, even at low doses, and without resulting in addiction.

Fallout: The Wrong Takeaways, The Wrong Target

Instead of learning that:

- Multiple treatments can help

- Low-dose opioids may be effective and safe

- Patients should have individualized options

Officials took away:

- “Opioids don’t help anyone”

- “High doses are unjustified”

- “We need to restrict access and punish providers”

This has led to:

- Thousands of forced tapers

- Countless ER visits for untreated pain

- Increased suicides and suffering

- Patients being labeled with OUD who were never misusing

All based on a study that never showed what they say it did.

🎯Section 6: What the Study Really Means

The SPACE Trial was never a sweeping judgment on opioids — it was a limited, controlled comparison of two treatment strategies in a small, specific group of patients. And when you strip away the headlines, soundbites, and litigation spin, here’s what it actually tells us:

Opioids Can Work — Even at Low Doses

Despite the study using low-dose opioids (~22 MME/day), many patients saw improvement:

- Pain intensity dropped

- Function improved

- Anxiety was reduced

Over 59% in both groups had a ≥30% improvement in pain-related function — including the opioid group, even with a modest dose.

It Doesn’t Justify Forced Tapering or Denial of Care

The trial did not:

- Study people with complex, long-term chronic pain

- Include anyone already on opioids

- Test what happens when opioids are taken away

- Show harm from long-term opioid therapy

Yet it's being used to justify cutting off care for patients it didn’t even study.

It Reported Zero Cases of Addiction, Misuse, or Overdose

Out of 240 patients, there were:

- 0 cases of OUD

- 0 cases of doctor-shopping or diversion

- 0 overdose deaths

Even PROP and addiction medicine advocates can’t point to this study as evidence of harm — because there was none.

It Was Misused to Support a Litigation Narrative

The SPACE Trial was used as “evidence” that opioids are ineffective — but only after being spun by advocacy groups, media, and expert witnesses who stood to benefit financially or politically. This wasn’t science speaking. It was strategy.

The Authors Themselves Admitted Its Limits

Even Dr. Erin Krebs, the lead author, acknowledged:

“It’s a bit too early for our study findings to be incorporated into guidelines.”

She also admitted that critics of the study were dismissed as "industry-funded," rather than actually addressing concerns about misapplication.

Final Takeaway

This trial was never meant to be the final word on opioid therapy.

But it was taken that way — and used to create a policy environment where:

- Pain patients were cut off

- Doctors were punished

- Opioid therapy was demonized

- And truth was buried under spin

It’s time to stop misusing this study — and start rebuilding pain care on evidence, not ideology.

Free Printable Resources: Please subscribe (free) to our Patreon Page for:

- Printable Summary

- Q&A for patients and advocates

- Myths v Facts

- Details

- Hits: 2902

💥 Debunking the Lie: “80% of Heroin Users Started with a Prescription from Their Doctor”

For free printable resources such as Q&A and Myth v Fact, subscribe (free) to our Patreon page

⚠️ TL;DR:

The “80%” statistic comes from a 2013 SAMHSA report that referred to nonmedical use of prescription opioids—not prescriptions from doctors.

Most heroin users did not start with their own legitimate pain care.

The data has since changed dramatically. As of 2015, 32% of people with OUD initiated with heroin, not pills. Today, illicit fentanyl is the primary driver of overdose—not prescribed opioids.

Despite this, the myth has been used to:

-

Justify restrictive prescribing policies

-

Push pain patients off medication

-

Expand Suboxone markets

-

Win massive legal settlements based on inflated addiction stats

This false narrative has led to widespread patient abandonment, stigma, and suicide—not because of addiction, but because people in pain were treated like they had an addiction.

It’s time to stop using this myth to shape policy.

📚 Table of Contents:

- Where Did This Stat Come From?

- Misuse ≠ Prescribed Use

- How the Language Changed — and Why That Matters

- How Inflated Stats Fueled Profit and Litigation

- What the Data Actually Shows

- What About the People Who Did Start with a Prescription?

- Real-World Consequences for Pain Patients

- Why It’s Time to Retire the “80%” Stat

- Call to Action

- Citations

1. Where Did This Stat Come From?

The claim that “80% of heroin users started with a prescription from their doctor” traces back to a 2013 report by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). But the actual data doesn’t say that at all.

What the SAMHSA report actually stated was:

“Nearly 80 percent of recent heroin initiates had previously used prescription pain relievers nonmedically.”

— SAMHSA, 2013

Keyword: “nonmedically.” This refers to people who used prescription opioids without a prescription, or in ways not intended by the prescriber (e.g., to get high, or taking a higher dose than prescribed). It does not mean they were prescribed opioids for pain and then progressed to heroin.

Despite this, the stat was quickly distorted by media outlets, policymakers, and advocacy groups. It morphed into the idea that 80% of heroin users were first given opioids by their doctor, which is false.

How It Got Twisted

In public debates, the nuance was lost. The phrase “nonmedical use” was dropped, and soundbites like “80% of heroin users started with a prescription” became common talking points. Organizations like Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing (PROP) used the statistic to promote more restrictive prescribing guidelines—framing it as proof that doctors and pain prescriptions were “creating addicts.” Media headlines ran with it, reinforcing the false link between medical prescribing and heroin addiction. But when researchers and journalists revisited the original data, they found something very different.

“What the data shows is not that 80 percent of people who use heroin were introduced to opioids through a doctor's prescription, but rather that they used opioids—somehow—before they tried heroin.”

— Politico Magazine, 2018

2. Misuse ≠ Prescribed Use

One of the biggest problems with the “80%” statistic is how it conflates two very different things:

👉 Misuse of prescription opioids vs 👉 Medical use under a doctor’s care

The 2013 SAMHSA report that spawned the stat was clear: it referred to people who had used prescription opioids nonmedically—meaning they didn’t take the medication as directed or didn’t have a prescription at all. In fact, SAMHSA defines nonmedical use as:

“Use of prescription pain relievers without a prescription of one’s own or simply for the experience or feeling the drugs caused.”

— SAMHSA, 2013

That includes:

- Borrowing pills from a friend

- Buying pills from a dealer

- Taking leftover pills to get high

- Using higher doses than prescribed

None of this is the same as a legitimate patient taking medication as prescribed by a doctor. Yet the “80%” soundbite erased that distinction—and in doing so, painted millions of patients as potential heroin users.

Misuse Was Never About Doctors Prescribing

According to a 2016 SAMHSA short report, nearly 54% of people who misused prescription pain relievers got them from friends or relatives—most often for free. Only 37.5% got them from a healthcare provider of any kind.

“Among people aged 12 or older who misused pain relievers in the past year, 53.7% obtained the last pain relievers they misused from a friend or relative.”

— SAMHSA, 2016

Actual Prescribing ≠ Gateway to Heroin

When NIDA reviewed this data in 2018, they came to the same conclusion:

“Although some people who misuse prescription opioids may transition to heroin, research suggests that heroin use is rare in people who use prescription opioids as directed, even among those with long-term medical use.”

— NIDA Research Report

In other words, taking opioids for pain from a doctor's Rx doesn’t often lead to heroin use. The transition is more common in people who were already misusing drugs—and even then, it’s far from inevitable.

3. How the Language Changed - and Why That Matters

Over the past decade, public health agencies began phasing out the term “drug abuse” from federal reports and surveys, citing concerns about stigma. In its place, they introduced more neutral-sounding terms like “use” and “misuse.” While the change was framed as compassionate, it had serious consequences—especially for people with pain. Instead of reducing stigma, the vague new language made it easier to blur the line between addiction and medical treatment.

“Misuse” Is a Vague, Dangerous Term

According to SAMHSA, misuse includes:

- Taking medication without a prescription

- Taking someone else’s medication

- Taking more than prescribed

- Taking less than prescribed

- Using medication for the “experience or feeling it causes”

This means someone who takes an extra pill during a pain flare—or uses a leftover prescription responsibly—can still be labeled as misusing opioids. Even patients on stable, long-term therapy have been swept into this category, simply for using medication in a way that’s technically outside the original instructions. This vague terminology allowed researchers, reporters, and policymakers to cite inflated statistics on “misuse” without clarifying that most of it had nothing to do with doctors or addiction. The result? It created the illusion that pain patients were fueling the overdose crisis.

DSM-5 Made Things Worse

At the same time, the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition) introduced a new diagnosis: Substance Use Disorder (SUD). It replaced the older, more distinct categories of “abuse” and “dependence” with a single diagnosis measured on a severity scale. While this was meant to reflect addiction as a spectrum, it collapsed key distinctions—especially for patients who were physically dependent on opioids but not addicted.

For example, long-term opioid therapy can result in:

- Tolerance (needing more to get the same effect)

- Withdrawal symptoms if stopped suddenly

- Continued use despite risks (like losing access to a prescriber or being flagged in a PDMP)

These are normal physiological responses—but under DSM-5, although they aren't supposed to can count toward a diagnosis of Opioid Use Disorder (OUD), they often are.

"Our findings suggest that the new OUD criteria may lead to a high rate of false positives when applied to patients maintained on chronic opioid therapy."

— Cicero et al., 2017 (PubMed)

The Impact on Pain Patients

These shifts in language and diagnosis laid the foundation for:

- Mislabeling people as having a “use disorder” when they didn’t

- Collapsing all opioid use—prescribed or not—into one broad category

- Justifying increased surveillance, forced tapers, and treatment mandates

- Feeding flawed data into risk-scoring tools and policy decisions

By redefining normal medical use as “misuse” or “disorder,” these changes didn't destigmatize drug use—they reshaped the entire narrative around opioids, often at the expense of patients who were simply trying to manage their pain.

4. How Inflated Stats Fueled Profit and Litigation

The shift in language and diagnostic criteria didn’t happen in a vacuum. Once terms like “misuse” and “use disorder” became broad enough to apply to stable patients, those inflated numbers didn’t just stigmatize—they funded an entire industry.

Behind the scenes, there were powerful financial and legal incentives to inflate opioid misuse and addiction statistics. This wasn't just a narrative mistake. It was part of a coordinated strategy that served:

- Addiction treatment companies

- Opioid litigation firms

- State and federal agencies managing settlement funds

Expanding the Suboxone Market

Companies like Indivior, which markets Suboxone, had a direct interest in expanding the definition of “opioid use disorder” (OUD). The broader the diagnosis, the more people qualified for medication-assisted treatment (MAT), sometimes called MOUD—including many pain patients who weren’t addicted. Once DSM-5 loosened the criteria and federal language blurred the lines, MOUD could be pushed as a solution for nearly anyone taking opioids. This expanded the customer base dramatically—regardless of whether patients benefited or needed it.

Feeding the Opioid Litigation Narrative

The opioid multidistrict litigation (MDL) was one of the largest legal efforts in U.S. history, involving thousands of cities, counties, and states suing opioid manufacturers and distributors. To win these cases, plaintiffs had to show that prescription opioids caused widespread addiction. The more people labeled with OUD—especially if they had ever filled a prescription—the stronger the legal claim. This is why blurring the line between misuse and medical use was so effective. It allowed lawyers and public health officials to retroactively blame prescribing for addiction cases that had nothing to do with a patient’s own treatment.

The now-debunked “80% stat” was the perfect tool—it seemed to offer a simple, compelling link between doctors and heroin, even if it was entirely misleading.

Abatement Funds Followed the Numbers

After the settlements were reached, billions of dollars were allocated to states and local governments to “combat the opioid crisis” through abatement funding. But the formula for who got how much? That often depended on how many people in a given area were labeled with opioid use disorder.

This created a perverse incentive:

- The more people diagnosed with OUD—even if misdiagnosed—the more funding states received.

- The more patients relabeled as “addicted,” the more justification there was to expand addiction infrastructure—even when that wasn’t what patients needed.

Instead of helping the people harmed by these policies, the money often went to build addiction treatment systems, criminal justice programs, and MOUD infrastructure—sometimes led by the very groups who helped distort the narrative in the first place.

This system created a self-reinforcing cycle:

- Change the definitions of misuse and addiction

- Inflate the number of people diagnosed with OUD

- Use those inflated numbers to win lawsuits and secure funding

- Funnel money into systems that continue the mislabeling

- Abandon the very patients whose data helped generate the payouts

And through it all, pain patients—many of whom were never addicted—were left out of the conversation, labeled as risks, cut off from care, and told they were part of the problem.

5. What the Data Actually Shows

The claim that “80% of heroin users started with a prescription from their doctor” falls apart the moment you actually look at the data. Research over the last decade shows that:

- Most people who use heroin did not start with their own opioid prescription

- Heroin use is rare among people who take opioids as prescribed

- Misuse is more likely to begin with pills obtained from friends, family, or dealers—not from a doctor

The “80%” statistic is not only misleading—it’s outdated.

Heroin Use Rarely Starts with Prescribed Use

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) has repeatedly emphasized that heroin use is not common among people who are prescribed opioids for legitimate medical reasons:

“Research suggests that heroin use is rare in people who use prescription opioids as directed, even among those with long-term medical use.”

— NIDA Research Report

In other words, taking opioids for pain—under the care of a doctor—is not what drives people to heroin. The vast majority of pain patients do not transition to illicit drug use.

Where Do People Really Get Pills?

According to a 2016 SAMHSA short report, over 53% of people who misused prescription pain relievers got them from friends or relatives, not a prescriber:

“Among people aged 12 or older who misused pain relievers in the past year, 53.7% obtained the last pain relievers they misused from a friend or relative.”

— SAMHSA, 2016

Only 37.5% got them from a healthcare provider—and that number includes not just patients, but also people who lied, forged prescriptions, or engaged in “doctor shopping.” The idea that doctors handing out prescriptions led directly to heroin use is not supported by how people actually access pills.

The Real Origin of the 80% Myth

The infamous stat originated from a 2013 SAMHSA report, which said:

“Nearly 80 percent of recent heroin initiates had previously used prescription pain relievers nonmedically.”

— SAMHSA, 2013

This quote is technically true—but deeply misleading.

It doesn’t say those people were prescribed opioids. It says they used them nonmedically—a category that includes:

- Taking leftover pills from a friend

- Buying pills on the street

- Using medication without a prescription

- Taking a higher dose than directed to get high

Even SAMHSA’s own definition of “nonmedical use” makes it clear this has nothing to do with being a legitimate pain patient.

Studies Confirm the Pattern Has Shifted

A 2019 analysis by Cicero et al., published in Addictive Behaviors, tracked how opioid use initiation has changed over time. It found that by 2015, 32% of people entering treatment for OUD said they first used heroin—not pills.

“Among individuals entering treatment for heroin use, the percentage who report initiating opioid use via prescription drugs has declined significantly since the early 2000s.”

— Cicero et al., 2019

This completely undermines the idea that most heroin users started with prescription opioids—and it shows that the “80%” claim is not just misleading, but obsolete.

6. What About the People Who Did Start with a Prescription?

It’s true that some individuals who use heroin or develop opioid use disorder (OUD) did first receive a prescription for opioids. But this group is smaller than often claimed, and their experiences are far more complex than the “gateway” myth suggests. Simply acknowledging that a person was prescribed opioids doesn’t explain how or why their use escalated—or whether it ever did.

Some Cases of Iatrogenic Addiction Exist — But They're Rare

Iatrogenic addiction (addiction caused by medical treatment) is real, but rare. Studies consistently show that the risk of developing a use disorder from opioids prescribed for pain is low when used appropriately.

“The risk of addiction during chronic opioid therapy is difficult to determine, but estimates from large, high-quality prospective studies are generally low, ranging from 0.6% to 8%.”

— Volkow & McLellan, NEJM, 2016

(Link to article)

This risk is not zero, and those who do develop OUD deserve support and care—but they should not be used as evidence that prescribing itself is the cause of the crisis, or that all patients on opioids are at high risk of addiction.

Many Were Abandoned, Not Addicted

For others, the transition to illicit opioids came not from addiction—but from desperation:

- Some were cut off suddenly due to policy shifts, insurance denials, or PDMP flags.

- Others were forcibly tapered, leaving them in withdrawal without alternatives.

- A number of people began using illicit opioids only after being denied adequate pain care.

In these cases, the problem wasn’t overprescribing—it was abandonment. And - instead of acknowledging these failures, policymakers used these patients as “proof” that prescribing opioids leads to heroin, turning individual tragedies into political tools.

Pain Patients and People Who Use Drugs Deserve Different Care Plans

Public health messaging often collapses all opioid users—prescribed or not—into the same category. But the motivations, health needs, and treatment strategies are not one-size-fits-all.

- A person with a decades-long pain condition who takes medication daily to function is not the same as someone using street fentanyl or heroin.

- One may need medical stability and continuity of care.

- The other may need harm reduction, housing, or addiction treatment.

- Both deserve compassionate treatment that is for the condition they have.

By ignoring this distinction, the system continues to punish both groups: pain patients are criminalized and cut off, while people who use drugs are pushed into narrow, sometimes coercive treatment pathways that don’t address their broader needs.

Misusing Tragedy to Justify Harm

Every overdose is tragic. Every life lost matters. But using the rare cases of iatrogenic addiction to justify blanket restrictions, forced tapers, and medical abandonment is not prevention—it’s exploitation.

Instead of asking:

“How do we prevent addiction?”

We should also be asking:

“How do we stop mislabeling patients?”

“How do we treat pain without creating more harm?”

“How do we prevent desperation—not just addiction?”

7. Real-World Consequences for Pain Patients

The myth that “80% of heroin users started with a prescription” didn’t just distort public understanding—it shaped real policies that devastated real people. By framing pain care as the source of addiction, lawmakers and health agencies built a system that prioritized punishment and control over compassion and individualized treatment. As a result, millions of people with chronic pain have suffered—not because of addiction, but because they were treated like they had an addiction.

Forced Tapers and Abandonment

Following the release of the CDC’s 2016 opioid guideline—heavily influenced by the “80%” narrative—doctors across the country began forcibly tapering patients off their long-term opioid medications. In many cases, they didn’t taper at all—they cut patients off completely, fearing legal consequences, licensing board scrutiny, or PDMP risk flags.

Even though the CDC later clarified that the guideline was misapplied, the damage was already done. The result?

- Patients forced into withdrawal

- Loss of mobility and return of severe pain

- Increased emergency room visits, depression, and suicidality

- An uptick in illicit drug use—not because patients were addicted, but because they were desperate for relief

Surveillance and Stigma

The idea that pain patients are “potential addicts” led to the widespread use of Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs) and tools like NarxCare, which assign algorithmic “risk scores” based on prescriptions—often without transparency or consent.

Patients flagged as “high risk” may:

- Be denied care without explanation

- Have surgeries or procedures canceled

- Lose access to long-term providers

- Be labeled with opioid use disorder in their electronic health record—even without meeting diagnostic criteria

This isn’t just stigma—it’s systemic discrimination based on a myth.

Broken Trust, Broken Systems

Many pain patients no longer trust the healthcare system. They’ve been gaslit, disbelieved, flagged, and abandoned. In some cases, patients have died—by suicide, by overdose, or from complications of untreated pain. And while public health officials continue to frame opioid policy around misuse prevention, very little attention is given to the harm caused by that very prevention strategy. Pain care has become a casualty of the opioid narrative. And that narrative was built, in part, on the false premise that “most heroin users started with a prescription.”

8. Why It's Time to Retire the "80%" Stat

The claim that “80% of heroin users started with a prescription from their doctor” has been used to justify some of the most harmful policies in modern medicine. It’s a distorted interpretation of outdated data, and it has been weaponized to vilify pain patients, criminalize prescribing, and fuel a legal and financial machine built on oversimplification. It’s time to let it go.

It’s Misleading by Design

The original SAMHSA report never said that heroin users were prescribed opioids. It said they had used prescription opioids nonmedically—a completely different claim. But the nuance was stripped away in favor of a soundbite that served a purpose: blame doctors, blame pills, and ignore context.

That false narrative became a cornerstone of:

- The 2016 CDC opioid guideline

- Risk-based PDMP surveillance tools

- The opioid multidistrict litigation (MDL)

- Addiction medicine marketing strategies

- Public health policy that punished legitimate patients

It’s Outdated and Irrelevant

Even if the stat had once reflected part of the picture, it no longer does. As of 2015, studies show that at least 32% of people with opioid use disorder began with heroin, not pills. Today, the crisis is driven overwhelmingly by illicit fentanyl and contaminated street drugs—not by pain patients or prescriptions. Continuing to cite this stat is not just misleading—it’s irresponsible.

It Hurts the People It Claims to Help

By collapsing all opioid users into one group, this narrative has fueled:

- Forced tapers

- Medical abandonment

- Inaccurate diagnoses

- Worsening disability and despair

- A healthcare system that treats patients as liabilities

- The very people who are supposed to be protected by policy—patients, people who use drugs, people with pain—have been the most harmed by the misuse of this statistic.

Let’s Move Forward With Facts

We don’t need myths to advocate for better care or address addiction. What we need is:

- Accurate data

- Clear distinctions between medical use and misuse

- Policies that protect patients without punishing providers

- Language that reflects complexity, not ideology

It’s time to stop building policy on a lie. Let this be the last time anyone uses the “80%” stat unchallenged.

9. Let's Move Forward With Facts - Call to Action

The myth that “80% of heroin users started with a prescription” has caused widespread harm—to truth, to policy, and to people. It’s time to replace this false narrative with facts.

What You Can Do:

🛑 Stop repeating the myth.

If you’re in public health, media, academia, or policy: don’t cite the “80%” stat. If you see others use it, challenge it. Ask for the source—and look at what it really says.

📣 Correct the record.

Speak up when you hear this myth repeated in articles, legislative hearings, grant proposals, or addiction medicine training. Redirect the conversation to real data.

⚖️ Demand policy based on evidence, not slogans.

Policies should distinguish between patients on stable opioid therapy and those with opioid use disorder. One-size-fits-all doesn’t work—and often causes harm.

🩺 Support care, not punishment.

Urge lawmakers, medical boards, and health systems to stop using flawed statistics to justify forced tapers, NarxCare flagging, or denial of care. Push for reforms that protect both pain patients and people who use drugs.

💡 Educate others.

Use this article, the data, and the citations provided to inform others—especially those in positions of influence. The more people understand the truth, the harder it becomes for myths to survive.

Let the Myth Die Here

The overdose crisis is real. The suffering is real. But using a distorted, outdated stat to explain it doesn’t help anyone—and it actively hurts people who are already marginalized and dismissed.

It’s time to retire the “80%” lie for good.

Let facts lead. Let patients speak. Let truth replace fear.

📖Citations:

-

SAMHSA (2013) – Associations of Nonmedical Pain Reliever Use and Initiation of Heroin Use

🔗 https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/DR006/DR006/nonmedical-pain-reliever-use-2013.htm -

SAMHSA (2016) – Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health

🔗 https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR1-2016/NSDUH-FFR1-2016.pdf -

Cicero, T. et al. (2018) – Increased Use of Heroin as an Initiating Opioid of Abuse

🔗 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30006021/ -

NIDA – Prescription Opioids and Heroin Research Report

🔗 https://nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/prescription-opioids-heroin/introduction -

Pain News Network (2018) – Do 80% of Heroin Users Really Start With a Prescription?

🔗 https://www.painnewsnetwork.org/stories/2018/4/23/do-80-of-heroin-users-really-start-with-a-prescription -

Politico (2018) – The Myth of What's Driving the Opioid Crisis

🔗 https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2018/02/21/the-myth-of-the-roots-of-the-opioid-crisis-217034 -

Volkow, N. & McLellan, A. (2016) – Opioid Abuse in Chronic Pain — Misconceptions and Mitigation Strategies

🔗 https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra1507771

For free printable resources such as Q&A and Myth v Fact, subscribe (free) to our Patreon page

Lie: "Opioid Induced Hyperalgesia (OIH) is a proven common condition where opioids make pain worse."

- Details

- Hits: 4942

💥 Debunking the Lie: “Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia (OIH) is a Proven, Common Condition Where Opioids Make Pain Worse.”

⚠️ THE TRUTH:

OIH is rare, often misunderstood, and frequently misused to justify dangerous tapers or abandonment of chronic pain patients.

Despite no definitive test, inconsistent evidence, and lack of consensus, it’s now regularly used to deny opioid treatment to people who are stable and doing well.

📚 TL;DR:

- OIH is a theory, not a diagnosis.

- Most research is in animals, not humans.

- No clinical test exists.

- It’s often confused with tolerance or withdrawal.

- Some doctors use OIH as a reason to cut off stable pain patients.

- No strong evidence supports OIH in chronic pain patients.

For more resources about OIH including a printable Q&A document for you to take to your doctor, subscribe to the free section of our Patreon Page

🧭 Topics Covered:

• What is OIH?

• Common Terms

• History of the OIH Concept

• Animal Studies vs. Human Truth

• The 5 Patient Populations in OIH Research

• Problematic Diagnosing of OIH

• What the Research Actually Shows

• Additional Studies on OIH

• Expert Opinions

• FDA Labeling of OIH

• Real-World Harm from the OIH Myth

• Who Benefits from Promoting OIH?

• What You Can Do

• Final Takeaway

Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia (OIH) is the theory that long-term opioid use causes your nervous system to become more sensitive to pain. In other words: “Your pain meds are making your pain worse.”

This concept is now widely used to justify tapering or stopping opioids — even for patients who are stable, functioning, and doing well. But the reality is:

- There’s no clinical test for OIH

- It’s often confused with tolerance, withdrawal, or inadequate pain control

- The evidence is inconsistent and weak, especially for chronic pain patients

-

Withdrawal: Temporary symptoms after reducing or stopping opioids — often includes rebound pain

-

Allodynia: Pain from things that shouldn’t cause pain (e.g., light touch)

-

Hyperalgesia: An exaggerated pain response to a painful stimulus

-

Central Sensitization: A chronically overactive nervous system, often seen in fibromyalgia, EDS, and complex pain

-

QST (Quantitative Sensory Testing): A research tool used to measure pain thresholds — not used in regular clinical practice

📜 Where Did the Idea Come From?

The first mention of opioid-induced pain came from Dr. Albutt in 1870, but no data was provided. Modern interest grew after animal studies showed rats reacting to opioids with increased pain. These findings were taken out of context and applied to humans — even though:

- Rats aren’t humans

- Doses in the studies were extremely high

- Most studies lasted only a few days

“Almost all the evidence for OIH comes from animal models.”

📄 Chu et al., 2008 — Link

🐀 Most OIH Research Is Based on Animals

But in the real world, chronic pain patients are typically on stable doses over months or years.

Yet most OIH studies:

- Use rodents

- Deliver huge doses

- Measure hotplate/tail-flick pain tests

- Focus on short-term use

🔬 The 5 Patient Populations in OIH Research

Pain researcher Dr. Erica Suzan, PhD reviewed decades of literature and categorized studies into 5 groups:

- Healthy Volunteers

- Acute Post-Operative Pain Patients

- Chronic Non-Cancer Pain Patients

- Cancer Pain Patients

- Patients on MOUD (e.g., Suboxone, Methadone)

These categories are drawn from key studies:

• Chu et al. (2008)

• Eisenberg, Suzan & Pud (2015) — Link

• Fishbain et al. (2009) — Link

1. Healthy Volunteers

Short-term opioid exposure

• Some studies showed mild hyperalgesia (possibly withdrawal)

✅ Not relevant to real-world long-term use

2. Acute Post-Surgical Pain Patients

Often confused with under-treatment or surgical pain

✅ Cannot be applied to chronic pain patients

3. Chronic Pain Patients

• Least studied group

• Most studies find no evidence of OIH

• Some studies find increased tolerance, not increased pain

4. MOUD Patients (e.g., Methadone, Suboxone)

• Some data suggests increased pain sensitivity

• Rarely discussed — politically sensitive issue

5. Cancer Pain Patients

• Almost no OIH research

• Disease progression likely causes increased pain

• Tapering opioids in this population is dangerous and unethical

🧪 Why Diagnosing OIH Is So Problematic

Doctors often say:

“We’re tapering you because you have OIH.”

But...

- There is no diagnostic test

- QST is a research-only tool

- Symptoms often mimic tolerance or disease progression

- Pain patients are often misjudged or dismissed

📄 Chu et al. (2008)

“Almost all the evidence comes from animal models.”

🔗 https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0b013e31816b2f43

📄 Eisenberg, Suzan & Pud (2015)

“True evidence in support of OIH is relatively limited... Most studies might have measured withdrawal or tolerance.”

🔗 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0885392414004023

Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia: A Research Phenomenon or a Clinical Reality?

📌 Canadian physician survey

• OIH suspected in only 0.01% of chronic pain patients

• Most providers didn’t use any test

• Conclusion: Rare, poorly defined, not consistently diagnosed

Analgesic Tolerance Without Demonstrable OIH

📌 Double-blind morphine trial on chronic low back pain

• Patients developed tolerance but not OIH

• First high-quality human study showing absence of OIH

🧠 Dr. Stefan Kertesz (@StefanKertesz)

“There is no proven way to diagnose OIH. Claiming it is often a smokescreen for dose reductions.”

💬 Dr. Bob Twillman (@BobTwillman)

“OIH is being used as an excuse to taper or discontinue opioids in a way that harms patients.”

The FDA added OIH language to opioid labels — but also admitted:

- There is no standard way to diagnose it

- These changes were likely political, not scientific

• Justify forced tapers

• Dismiss patients doing well on stable doses

• Label patients “drug-seeking”

• Push people toward rehab or Suboxone

• Abandon patients in crisis

Some have died by suicide after being told their pain was “caused by opioids” and then denied care.

🧨 Who Benefits From Promoting OIH?

• Addiction treatment networks that profit from Suboxone

• Lawmakers and public health officials looking to reduce opioid prescribing stats

• Rehab centers that replace pain care with detox

• Advocacy groups like PROP who use OIH to justify aggressive tapering campaigns

Ask your doctor:

• “How did you diagnose OIH?”

• “Could this be withdrawal, tolerance, or disease progression?”

• “Can we rotate opioids or adjust my dose instead of tapering?”

• “What research supports your recommendation?”

For more resources about OIH including a printable Q&A document for you to take to your doctor, subscribe to the free section of our Patreon Page

You have the right to ask questions. You have the right to safe, evidence-based care.

Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia has never been proven in chronic pain patients.

The only evidence comes from animal studies — not from real-world long-term opioid therapy.

It is a theory, not a diagnosis — and it's being misused to justify dangerous tapering, denial of care, and discrimination.

Don’t let them use a rat study to take away your treatment. 🐀

This content was written by DPF. Updated April 15, 2025

- Details

- Hits: 2859

💥 Debunking the Lie: “MME Limits Are a Scientific Concept”

⚠️ THE TRUTH: Morphine Milligram Equivalent (MME) limits are not based on science. They were developed as rough estimates for opioid conversions, not as risk tools, dosing caps, or policy triggers. Yet they’ve been weaponized across healthcare, law, and insurance to justify harmful denials, surveillance, and tapering of stable patients.

For additional free printable materials, subscribe (free) to our Patreon Page:

- Printable Q&A

- Printable Summary of Main Points

- Printable Myths v. Facts

TL;DR 📌

-

MME conversions aren’t scientific. They were designed to help switch opioids — not guide laws or treatment.

-

There’s no single MME formula. PDMPs, providers, and regulators all use different ones — often without transparency.

-

The 90 MME “limit” isn’t evidence-based. It came from a 2007 Washington State guideline based on opinion, not data.

-

The FDA rejected a 100 MME threshold. The CDC later included one anyway, and it was misused across the country.

-

The CDC reversed course in 2022. But systems still use the 2016 cap, causing patient abandonment and harm.

-

Until thresholds are de-implemented, the damage will continue — no matter what the new guideline says.

📚 Table of Contents

- What Is MME — and What Was It Supposed to Do?

- What the Science Says: How MME Conversions Are Calculated — and Why They Differ

- Where Did 90 MME Come From? The Origins of Arbitrary Thresholds

- How MME Became a Weapon: One Metric, Many Formulas

- How Are MME Thresholds Used in Policy?

- The Real-World Consequences: What Happens When MME Is Misused?

- Selective Use of MME: Pain vs. Addiction Treatment

- The NIH “Research-Only” MME Calculator

- How the DOJ and Law Enforcement Weaponize MME

- Policy Hypocrisy: Buprenorphine, Bias, and Enforcement Gaps

- Call to Action: Stop Using MME to Punish Patients

1️⃣ What Is MME — and What Was It Supposed to Do?